–

Wow! After 26 days, it’s finally over – let’s do a recap of what the toads were up to this year…

An Exceptional Year

Searching for toadlets along the survey route

By the middle of July it felt like we had been doing our toad survey route forever. As this year’s summer students, it was our responsibility to walk the 6 kilometer survey route that covered Elk View, Ryder Lake, and Houston Roads regularly to watch the marching army of tiny toadlets. Rain or shine, morning or evening, the two of us would painstakingly count every toadlet on the road that we could see, occasionally putting down our wooden sampling frame to take a closer look.

During the latter part of the migration, we had heard of some eyewitness accounts of toadlets crossing near the intersection of Ryder Lake and Extrom Road, well beyond our survey route. Being inquisitive researchers, we walked along the road to investigate. As we climbed the hill towards Extrom road, I became increasingly skeptical. There weren’t any toadlets to be found.

But then we reached the top of a hill and BAM! What seemed like tens or hundreds of toads were scattered across the road, like we had seen at the peak of the migration. I couldn’t believe my eyes.

This incident was just one notable example of how this year’s Western toadlet migration was exciting!

–

–

-.

–

.

Gathering the data

Counting toadlets in the survey plots

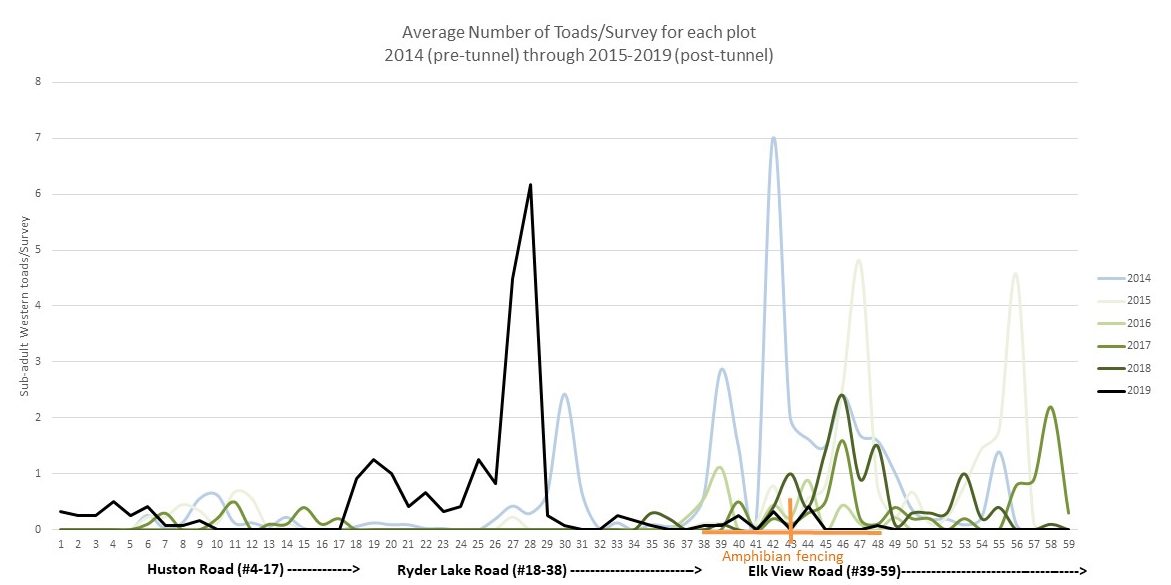

Why do we have to survey the toadlets when we already have a toad tunnel and fencing installed? Firstly, we want to see if we have reduced toadlet road mortality with these measures. Secondly, this is an opportunity to learn more about this population and track any migration trends.

Daily surveys are necessary to collect toadlet data for this project. We rely on the numbers from our road surveys to give us an idea of the scope of the migration. Our survey route is not a casual stroll; it is a stretch of road carefully divided into 57 plots that are 50 metres apart. In every plot, we put down a wooden sampling frame that we use to count toadlets. We also estimate the amount of dead and alive toads we see between each sampling frame. The road survey data is used to assess whether the toad tunnel and fencing are mitigation for road mortality.

What we have found so far

–

–

The toads were prolific this year! After tallying up our road plot counts, we discovered that there were about 10 times as many live toadlets in the plots compared to last year, and only twice as many dead. The abundance of toadlets can be explained by the large number of adults observed in the spring moving into Hornby Lake to breed. We found twice as many adults migrating to the breeding pond in 2018 as in 2017, and the number of adults observed doubled again this year. Their migration route heading west across Ryder Lake Road was a good choice for the toadlets in the sense that there is way less traffic on this road, significantly reducing the likelihood of being killed.

It was a big milestone for the breeding adults this year. The toads that came to Hornby to breed this year would have been part of the first cohort of toadlets to use the brand new tunnel in 2015!

As shown in our annual “toadlets on the road” graph above, the route the toadlets chose to exit the pond this year were somewhat different than in the last 4 years. More toadlets migrated across Ryder Lake Road this year, similar to 2014.

Volume and Radius

When I asked project lead Sofi Hindmarch about what set this year’s toad migration apart from the others, the keywords that really stuck out to me were “volume” and “radius”.

I couldn’t agree more with those descriptors. If we were to estimate how many toadlets made the mass exodus from Hornby Lake this year, our numbers would land in the tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands. Those mother toadlets did a great job filling up the pond with eggs!

The second keyword, radius, also characterizes the migration with the toadlets spreading out across several roads and migrating in all directions. We even saw toadlets in places we haven’t seen them before – near the intersection of Ryder Lake and Extrom road. While not many used the toad tunnel this year, this migration pattern may be a blessing in disguise. By crossing roads with less traffic more toadlets made it safely across the road.

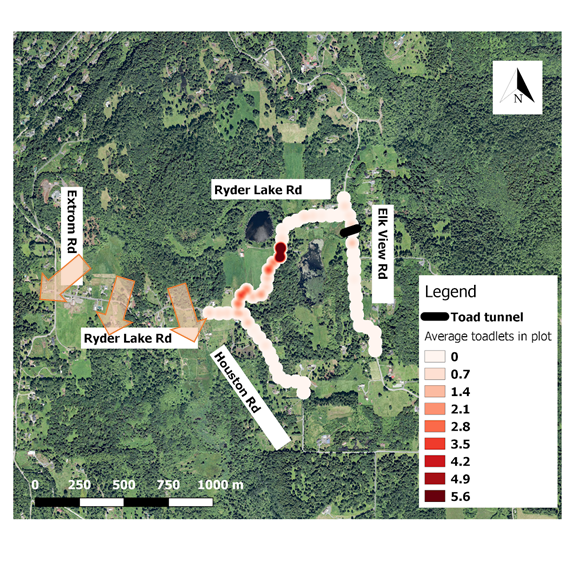

The density map above shows where the toadlets migrated out from the breeding pond. This year’s migration hotspot was across the stretch of Ryder Lake Road near the lake. However, they crossed in some capacity all along Ryder Lake Road, parts of Houston Road, and also near the toad tunnel.

The density map above shows where the toadlets migrated out from the breeding pond. This year’s migration hotspot was across the stretch of Ryder Lake Road near the lake. However, they crossed in some capacity all along Ryder Lake Road, parts of Houston Road, and also near the toad tunnel.

But what is that sound?

Something odd jumped out at us when doing our toad walks. Nearly every day when we passed by Ryder Lake we began to hear an unsettling sound. “It must be a cow who’s lost its calf,” I told my co-worker. After all, I had heard a similar noise from the herd of cattle by my house. But the sound was there seemingly without fail. As soon as Ryder Lake became visible through the trees, that awful noise like a broken seesaw would greet us. Unfortunately, it was indicative of something much worse than a cow.–

Folks, the bullfrogs have found Ryder Lake…

A bullfrog tadpole, compare to the toad tadpole at the top of this post!

‘Bullfrog’ is a word that can send shivers down an ecologist’s spine, at least here in B.C. But why is that? Other than breaking the local noise curfew, bullfrogs are an invasive species. The body of bullfrog tadpoles (not including the tail) can reach up to 6 centimeters in length – that’s up to 3 times the length of toad and tree frog tadpoles! In the breeding pond, bullfrog tadpoles can outcompete native amphibian larvae for space and food. Soon, what was once a diverse breeding pond becomes a bullfrog breeding pond. Once bullfrogs reach their full size they become even more of a menace. Adult bullfrogs, which can reach up to 20 centimeters in length, will eat anything that fits into their mouths.

–

–

One of our most dedicated Ryder Lake volunteers with a young bullfrog

On average bullfrogs take 4 years to reach breeding age, 2 years as a tadpole, and 2 years as an adult. Currently, all 4 of these life stages are present at Hornby Lake (the main breeding pond), meaning that they have been there for at least 4 years. Breeding adults are now at Ryder Lake as well, so the bullfrogs are spreading, and they will continue to do so until all ponds they can access are occupied.

However, now that the FVC knows of their presence at Ryder Lake we can assess the situation to see if there are feasible options to stop the bullfrog invasion. Currently we are consulting with Provincial experts on best practices to deal with bullfrogs. How do you tell the difference between bullfrogs and toads? What do you do if you find one? For answers to these questions and others, visit our previous post on the subject.

–

–

–

What a year!

Toadlet migrations are an exceptionally cool phenomenon and it was amazing to have the opportunity to observe these amazing creatures make their way towards their forest home. We learned a lot about the toadlets during their migration and were able to contribute to research on this population. Can’t wait to see what the toads do next year!

This project is made possible by support from:

As well as our wonderful FVC donors and volunteers – THANK YOU!