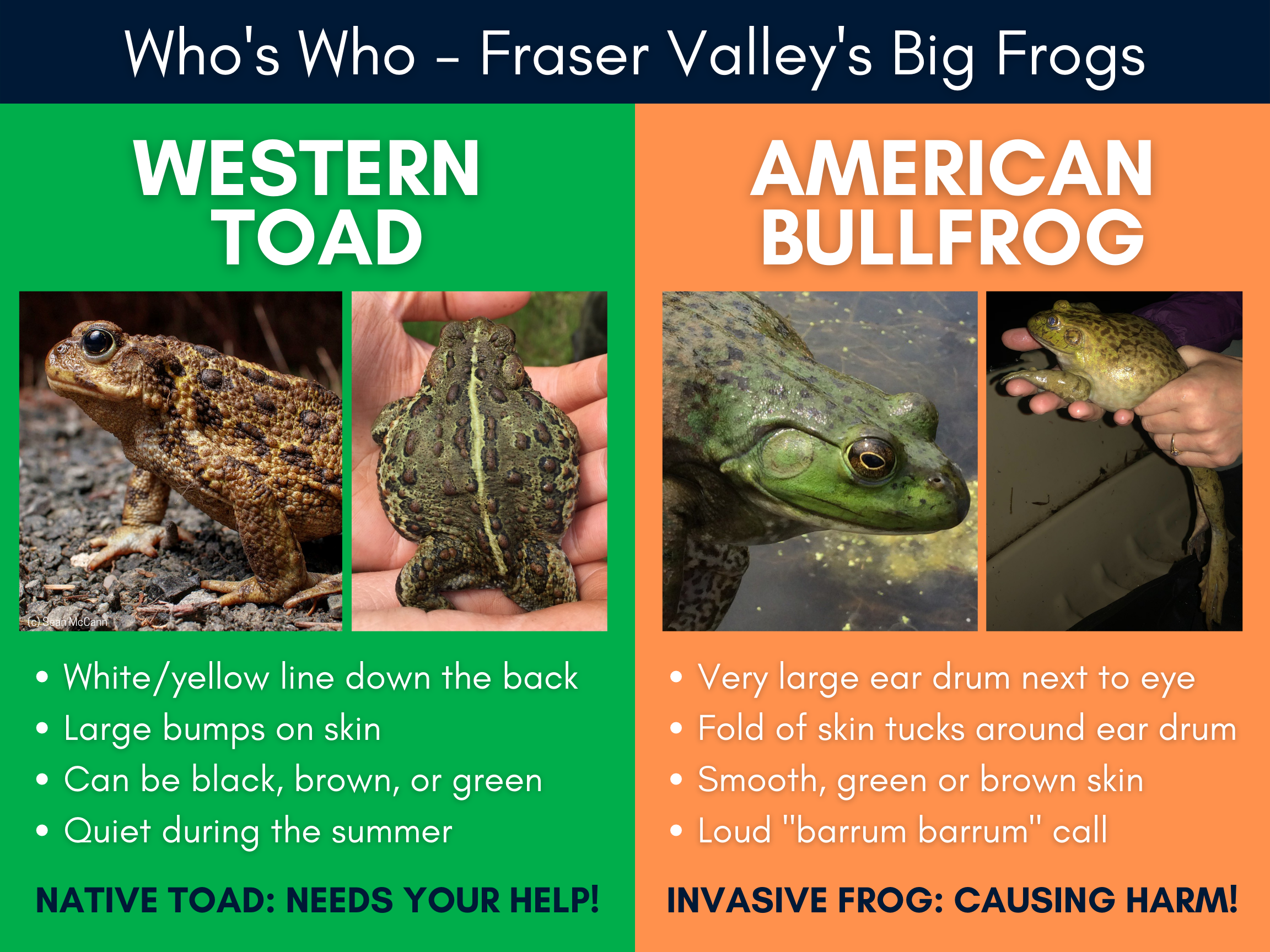

Every year, around the beginning of July, Fraser Valley residents start to hear the sound of invasive predators in their local wetlands. The loud “barrum barrum” mating call of the American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus) is certainly a distinctive sound.

Audio Player

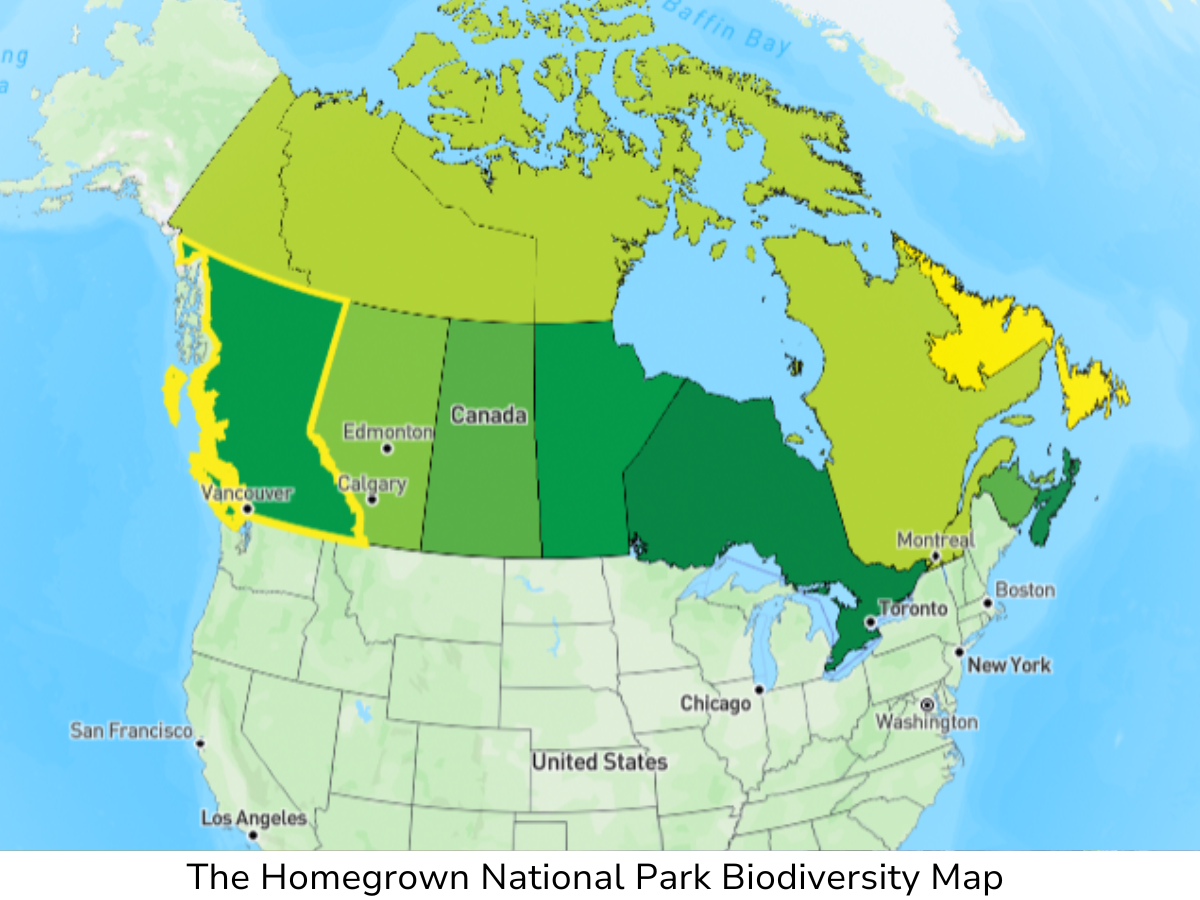

If you haven’t heard this bellowing call, consider yourself (and your local wildlife) lucky. Bullfrogs are invasive, meaning they are not indigenous to this area and are causing ecological harm. Native to Eastern Canada and the United States, Bullfrogs are not part of the natural ecosystem of the Fraser Valley. Bullfrogs reproduce quickly and can grow so big that natural predators (like herons, otters, hawks, and snakes) are less likely to try to eat them.

So, why don’t we just remove the Bullfrogs? Unfortunately, the situation is much more complicated than it seems.

There are two things you absolutely need to know:

Trying to control Bullfrogs can result in harming native species rather than helping them

The best thing we can do is leave Bullfrogs alone and focus instead on creating healthy habitats for our native species

Read on to learn more about the three major issues surrounding Bullfrog control in the Fraser Valley: Identification, Population Dynamics, and Purpose.